Broadway 1900-1918

During the time period from 1900-1918, Broadway was just beginning to develop as a cultural center in New York City. In its beginnings, Broadway was provincial and parochial, bearing no serious relation to art or life, and not taken very seriously by the general public. Characterized by charm and simplicity, the theater district attracted large audiences of middle class people in search of music, excitement, and romance, the best seats in the house only costing $1.50 to $2.00.

The theater district originated in 1900 on 13th Street where The Star theater was located, showing a play called "A Great White Diamond." Broadway extended to only 45th Street, where the New York Theater was playing "The Man in the Moon Junior" and "Broadway to Tokyo." Other productions at this time included "Way Down East" at The Academy of Music on 14th Street portraying the essential goodness of country people, and "Ben Hur" on 41st Street at the Broadway Theater. At the Madison Square Theater on 24th Street ran a production called "Coralie Company, Dressmakers" in which a white man is discovered in bed with a Negress, a play which was considered scandalous and shocked the public.

For the most part in this "Era of Good Feelings," the relationship between audience and actors was mostly cordial and unsophisticated, but lively and exuberant. Audiences often became very involved in the plays, sometimes talking to the actors, hissing, or clapping. All theaters at this time had a pit orchestra that played before the show, during intermission, and after the show, engaging the audience in music.

Before the United States entered World War One in 1917, Broadway theater did not deal with reality or social issues in its plays. One of the only plays that dealt with these ideas was a grim war play called "Moloch" by Beulah Marie Dix, produced in 1915 by George Tyler. This play dramatized distasteful topics, such as brutality and suffering. The public at this time, however, tended to stray toward other, more cheerful plays. Once the war began, Broadway plays were used as an escape from harsh reality. Dr. Frank Crane, the guru of 1917, in response to governmental desire to tax play tickets during the war, pointed out how amusement is essential to people during harsh times like war, stating "The stage is not a nations weakness, extravagance or undoing, but it is a nations deep refreshment that gives to the hearts and minds of a great people that spirit of courage and light and adventure that is needed to achieve success in the arena of world conflict."

Although Broadway plays were used mostly to escape the reality of the war, the Broadway community itself became very active in assisting the war effort. The play "Yip, Yip, Yaphank" at the Century Theater was used to raise money for the war relief, marking the climax of Broadways participation in the war in 1918. The show, written by Irving Berlin, was a conventional musical show, but it was equipped with soldiers who impersonated chorus girls, a cartoon of kitchen police called "Safe for Democracy", and the ballad "Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning." The show aroused the enthusiasm of thousands of Americans, and transformed the boredom of army life into humor.

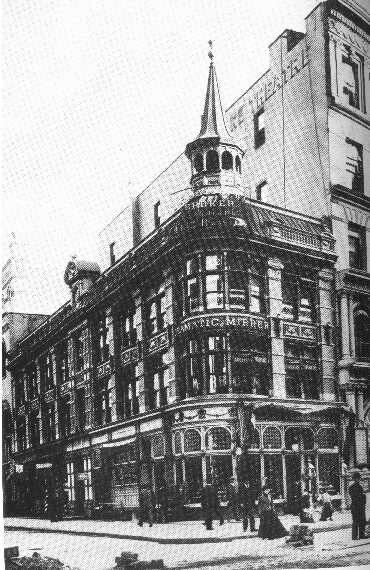

The Empire Theatre on Broadway and 40th Street

Broadway in the 1920s

After the war ended, Times Square became mobbed with crowds of enthusiastic citizens carrying flags and cheering, and the Times Tower was strung with electric lights for the celebration. Since this moment, Times Square has always been a gathering place for the entire city, drawing cheerful crowds to the spirited environment. During the 1920s, Broadway reached its prime. Many of the old buildings originally used for housing were now used to display signs, such as adds for "Lucky Strike" and "Pepsi Cola." One might describe Broadway at this time as being garish, and had a reputation of being cheap and tawdry. However an English writer, Stephen Graham wrote about Broadway at the time, "There is no garishness in it and it wells upward into that artificial light which is greater than the day." Paul Morand, a French novelist visiting New York agreed, "In Forty-second Street, it is a glowing Summer afternoon all night: one might almost wear white trousers and a straw hat. Theaters, night clubs, movie palaces, restaurants are all lighted at every porthole. Undiscovered prisms, rainbows squared." Broadway was never meant to be beautiful, but hoped that people would feel livelier in its "tonic light-bath," during its prime hour of night.

Although statisticians argue over exactly how many theaters there were some say eighty, some seventy everyone agreed that Broadway theaters were booming in the twenties. During these years, the number of productions increased from 126 in 1917 to 264 in 1928, which is still the all-time peak of Broadway production. During the twenties and after the war, the American population was moving more and more into the cities. The decade, known as the "Roaring Twenties," has been notorious in history for being a reckless, irresponsible, and materialistic era. In response to the many social changes occurring in America, the new plays on Broadway eliminated their old traditional storylines in the productions. In "What Price Glory?" the writer sent the message that war is not noble, but irrelevant. In "Desire Under the Elms," the life of the traditional American farmer degenerated into incest and greed. This collapse of tradition turned drama into a criticism of life, and surprisingly this was the best period in Broadway drama.

Overall in the 1920s, Broadway was bursting with energy and enterprise. The theater was filled with hope and fresh ideas, and new styles of craftsmanship. And with the organization of the Theater Guild by Lawrence Langner, Broadway became a brilliant center that influenced the theater of the world.

Broadway 1920's

Broadway in the 1930s

After the stock-market crash of 1929, and with the Great Depression overwhelming American politics and economics, Broadway undoubtedly plunged as well. The depression profoundly affected Broadway theater, causing the number of productions to decline dramatically, and putting many theater people out of work. Paradoxically, however, this was actually a creative period, perhaps because the depression had a dramatic feeling, inspiring creative works and exciting emotions. Established writers such as Eugene ONeill, George Kaufman, and Marc Connelly organized themselves into the Playwrights Company, and continued to write interesting plays that were often more concerned with the state of affairs in America than before.

Eugene O'Neill

At the same time since the American system seemed to be failing and the new Soviet system seemed possibly promising, many Broadway actors and theater people joined the Communist party. The Soviet Union subsidized its theaters and the actors in Moscow were actually making a living, which was attractive to the American actors and playwrights. As a result of this common shift to the Communist party, many off Broadway theaters now included dramas of social protest, using the slogan "Theater as a Weapon." The New Theater League and the Theater Union produced passionate dramas in order to propagandize the "working class," and left-wing productions became fashionable. Many playwrights used the theaters to make social commentary and advocate communist ideals to the public.

World War II

When the United States declared war on Germany and Japan in 1941, Broadway demonstrated that although it was liberal in politics and morals, it was conservative in its loyalty to the nation. The American Theater Wing separated from British War Relief to concentrate on American needs, quickly becoming a major Broadway industry drawing the talent and benevolence of hundreds of theater people. Many of these people involved in Broadway theater volunteered to help the war effort, doing tasks that ranged from addressing envelopes to writing stage sketches. The stage sketches were mostly done on themes that related to the public morale and workers in the war industries.

In 1942 the Wing opened the Stage Door Canteen in the 44th Street Theater, which was donated by the Shubert Brothers. It was a place that was meant to entertain and provide food for servicemen during their breaks from the war, and nearly everything offered there was free. Caterers and restaurants donated sandwiches, pies, coffee, and cakes, and waitresses and hostesses volunteered to work there. The place was originally intended to serve about five hundred servicemen, but the number turned out to be close to three or four thousand, including Americans, British, Canadians, Australians, Dutch, Chinese, French, and Russian. Some of the entertainers that came included Ethel Merman, Gracie Fields, and Ethel Waters. The theater was very successful, and had a long run.

World War II also inspired the United Service Organization, which was very closely tied to the government. In 1940 the USO offered Camp Shows to alleviate some of the boredom of the military life of the men who had been drafted. In 1941 the War Department asked the USO to be responsible for entertaining troops, and the government gave ample support to the cause. A huge USO sign was erected in Times Square that contained a portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt that said "The USO deserves the support of every individual citizen." Any person who walked through Times Sqaure would be made fully aware of the national emergency that was occurring during this time.

Broadway in the 1940s

During the 1940s, Broadway began to lose its originality and drive. New dramatists were less numerous, and Broadway began to face competition from television and movies. Some theaters were pulled down, and now theater no longer dominated Broadway.

Beginning in the thirties, and in the forties 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, the street most associated with Times Square, began to look less and less like a theater district. The theater business was declining all over the city to the point where there were not enough productions to support the available playhouses. In comparison to the 264 productions in 1927-1928, the number dropped to 187 in 1930-1931, and only 72 in 1940-1941. Times Square had degenerated into a kind of carnival and sex bazaar. The Republic Theater, which was built by Oscar Hammerstein in 1900, became Billy Minskys burlesque house. Theaters all over the area were being torn down or turned into slums.

Most theaters on Broadway were now film houses. Movies were beginning to take over the entertainment business, and theater as an industry had become obsolete, for now the increasing real-estate values made theater buildings uneconomical. In the beginning of the century, theaters were both a good investment and a symbol of vivacity and mirth. After World War II, however, theater buildings became unprofitable, and were sometimes considered dangerous after a fire in Chicago in 1902. Also by the 1940s television was becoming a worthy competitor for Broadway theater, providing the public with free entertainment. The result of all these pressures on Broadway theater was a shocking 80% unemployment rate for Broadway actors in 1948, and for the first time in its history, Broadway had to call a general emergency meeting for all the unions and theater people.

At this point Broadway had become less of an industry and more of a loose array of individuals, which by 1950 actually had certain positive aspects. This time period in America was one of increasing intolerance and political persecution, but Broadway was not afraid to express unorthodox opinions, and did not fear the government. Although Broadway theater had lost some of its scope, it still retained its liveliness and joyfulness in an increasingly corporate environment. In a country that now required conformity, Broadway preserved a sense of freedom of speech and action, ideals on which the nation was founded.

Broadway 1950-1970

After 1950, Broadway and the theater business continued their decline that began in the thirties. In 1969-1970 there were only 62 productions, 15 of which were revivals, and by 1969 there were only 36 playhouses left, compared to the 70 or 80 in the twenties. However Broadway was still attracting audiences from other parts of the country - approximately one-third of the people going to the theaters in New York were out of town visitors who often saw as many as five shows during their stay. At this time when New Yorkers were beginning to drift away from theater, the Louisville Courier-Journal and the Columbus (Ohio) CItizen organized "show trains." The newspapers would advise readers about the available productions, and then arrange transportation and hotel accommodations, and purchase the theater tickets. In the 1950's, Broadway became a popular holiday location.

Broadway theater was also being affected by the politics of the time. American people were becoming less and less optimistic about life in general, and spirits across the country were low. People were negatively influenced by such things as the hydrogen bomb and its inhuman implications, McCarthyism, the Vietnam and Korean wars, the Bay of Pigs incident, the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King, and the cold war in general. This atmosphere that was dominating the country was not at all conducive to the kind of vibrant and irresponsible theater on Broadway.

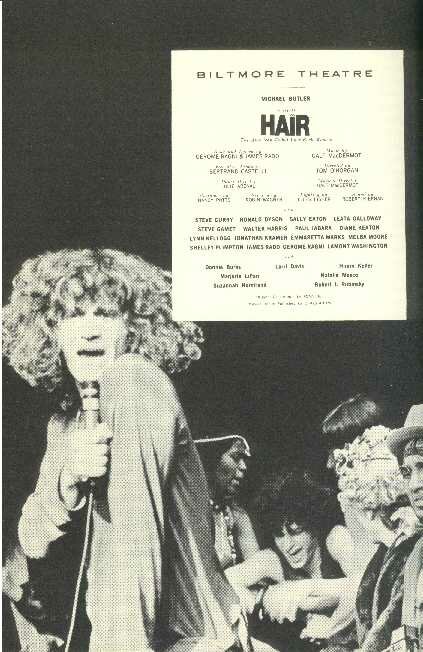

Despite the fact that Broadway at this time was depressed, there were many memorable musicals that emerged in 1950-1970. Some of these shows included West Side Story, The Music Man, My Fair Lady, Wonderful Town, The Most Happy Fella, The Sound of Music, Fidler on the Roof, Man of La Mancha, and Hair. Because it had become such a hysterical task to undertake a theater production at this time, only the most enthusiastic people would become involved, which would account for some of these extravagant musical plays that were produced during this time period.

Times Square 1950's (left) and The Musical Hair